The word “holocaust” comes from two Greek words, one meaning “whole” and the other meaning “burning”/”burned.” The connotation of the word implies a burnt offering, such as a sacrifice to a deity. In Schindler’s List, both the imagery of burning and the idea of sacrifice figure prominently, never letting the viewer forget the purpose of the film is to remember the Holocaust and honor its victims and survivors.

As noted in this week’s warm-up post, Schindler’s List is a black-and-white movie–but not all of the film is lacking color. In the opening scene, a Jewish family gathers around a table in their home. An older man sings, while the candles in two tall candlesticks burn. The camera focuses on the flame of one of the candles as it burns low, and very subtly the film morphs from color to black-and-white, after which the candle goes out with an upward stream of smoke. Several points seem to be made in this scene. First, we see the unity and harmlessness of the Jewish family and their religion. The scene is peaceful and hauntingly sad as the family disappears from view–just as millions of Jews disappeared forever during the Holocaust. The smoking candle also hints at the decimation of the Jews that will be pictured later in the film: What was strong and warm will become weak and then will be no more. Furthermore, there is the obvious connection with the definition of holocaust: The Jews will both literally (especially in the crematoriums of the death camps) and figuratively be burned up by the horror of the Nazis’ “Final Solution” to the Jewish “problem.” Perhaps one hopeful idea that one can draw from the smoldering candle is that the Holocaust will eventually burn itself out, its hatred and ignorance finally consuming it.

Another (and more famous) feature of Schindler’s List with a color connected to the idea of burning is the little girl in the red coat. She first appears during the German liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, one of the most violent scenes in the film. The little girl scampers around, unsure of what is happening and not knowing where to go. She walks by soldiers and enters tenements that have already been cleared of their residents. Eventually, she crawls under a bed, but the film’s viewers know that her hiding place is lame and she will be captured. Schindler stops at a place overlooking the ghetto while riding horses with his mistress and sees the little girl in the streets below. He is deeply moved by her plight, but does nothing to help her or anyone else. Much later in the film, the little girl appears again. Still dressed in her red coat, but now deceased, she is wheeled past a shocked Schindler on her way to the massive pile of burning Jewish bodies as the Nazis prepare to retreat in the face of the advancing Allied forces. The brief scene changes Schindler forever; he resolves to save as many of his Jewish workers as he can. The little girl herself, though physically annihilated in the Holocaust, also plays a symbolic role. Being so young and wearing the color red (red being clearly connected with fire and burning), the little girl again connects the innocence of the Jewish people with the horror of their massacre and immolation during World War II. She also, according to Steven Spielberg, represents how obvious it was to those in the highest levels of government in the Allied nations (especially the United States) that the Holocaust was occurring–still, those leaders did nothing to stop the killings, choosing instead to focus on winning the war.

Spielberg partly blames those Allied leaders for the millions of Jews who were forced to become sacrifices–actual burnt offerings–during the Holocaust. While there’s no denying the unfathomable price paid by the Jewish people during the second World War, the thing about sacrifices, at least in the Old Testament/burnt offering context, is that they must be given willingly. And that is not true of the Jews during the Holocaust. While many, if not most, surrendered their possessions, their rights, and their lives, they did so each time with the belief that their situation had gotten as bad as it could possibly be. Each new regulation, every additional limit to Jewish freedom was the height of what German racism must be able to imagine. Several Jewish characters express this misguided belief during the film, and they are always wrong. The Germans demanded every sacrifice of the Jews–even the incomprehensible surrender of their lives–but the Jews did not hand themselves over to the Germans willingly. They clearly wanted life and not the torture and death they were given.

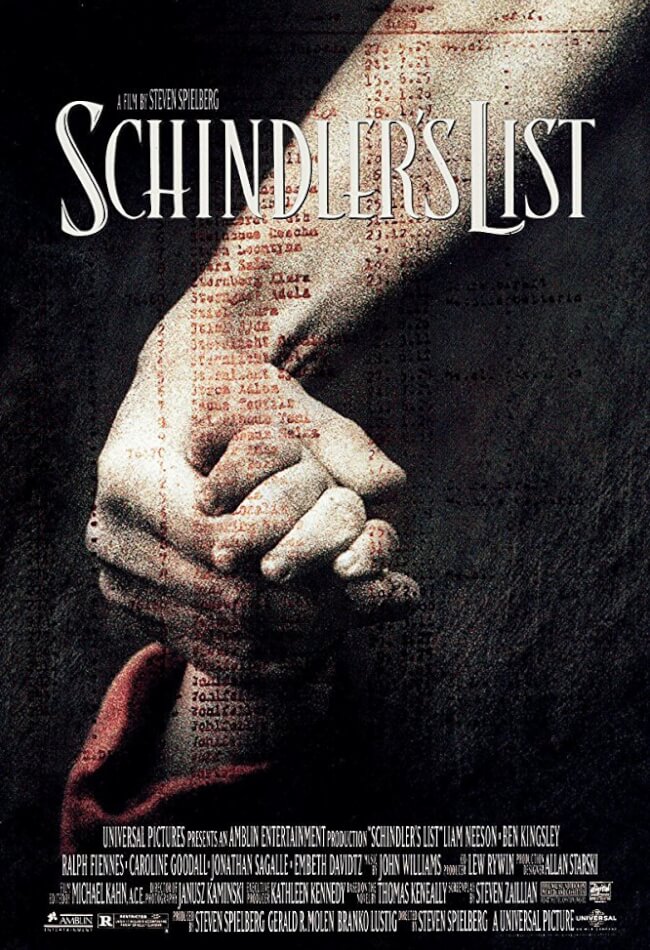

The character in Schindler’s List who does sacrifice willingly is Schindler himself. Though at first he’s only interested in money and women and worming his way into the “it” crowd of influential Nazis, by the end of the film, he has transformed into a man who gives everything he has–his women, his business, and his money–in order to save others. He is jokingly called Moses by the evil Amon Goeth–and Schindler is indeed a lot like the biblical hero in that he gives up a life of luxury to lead an enslaved people to eventual freedom. Thomas Keneally’s original title for his novel on which the film is based is called Schindler’s Ark, again emphasizing a biblical character (Noah) who lost much to save many.

For Me Then…

In their salvific roles, Moses and Noah can be seen as precursors of Jesus Christ, so it is interesting that a film focusing on Jews during the Holocaust contains a somewhat Christian message of hope and renewal. Schindler himself, with all his faults, makes a pretty lame Christlike figure–still, his rescue of over 1,200 Jews, as well as the sacrifice he must make to achieve this, puts an end to Jewish “burnt offerings” and ushers in a new period of life and restoration.

Like the beginning of the film, the end also features fire and color (spoiler alert!). Once he has rescued them, Schindler’s Jews are permitted again to celebrate the Sabbath–with candles like those they had at the beginning of the movie. And at the close of the film in a deeply moving (and full color) scene, the actual surviving Jews that Schindler saved, along with the actors who played them in the film, place rocks on his tombstone as a memorial. Here, the abandonment of black-and-white coloring again indicates renewal. The past will never be forgotten–nor should it be–but there is hope in the future because of people like Oskar Schindler, people who see the right and do it, despite the risk to themselves and in spite of the fact that they may never receive anything in return.